This is the second half of a two-part interview with serial entrepreneur and Forbes's Midas List venture capitalist Navin Chaddha. For more insider tips, read the first half of the interview.

Chaddha has worked on both sides of the investment aisle. He sold his first company to Microsoft in the 1990s, and he had the chance to work closely alongside Satya Nadella, now the software giant's CEO.

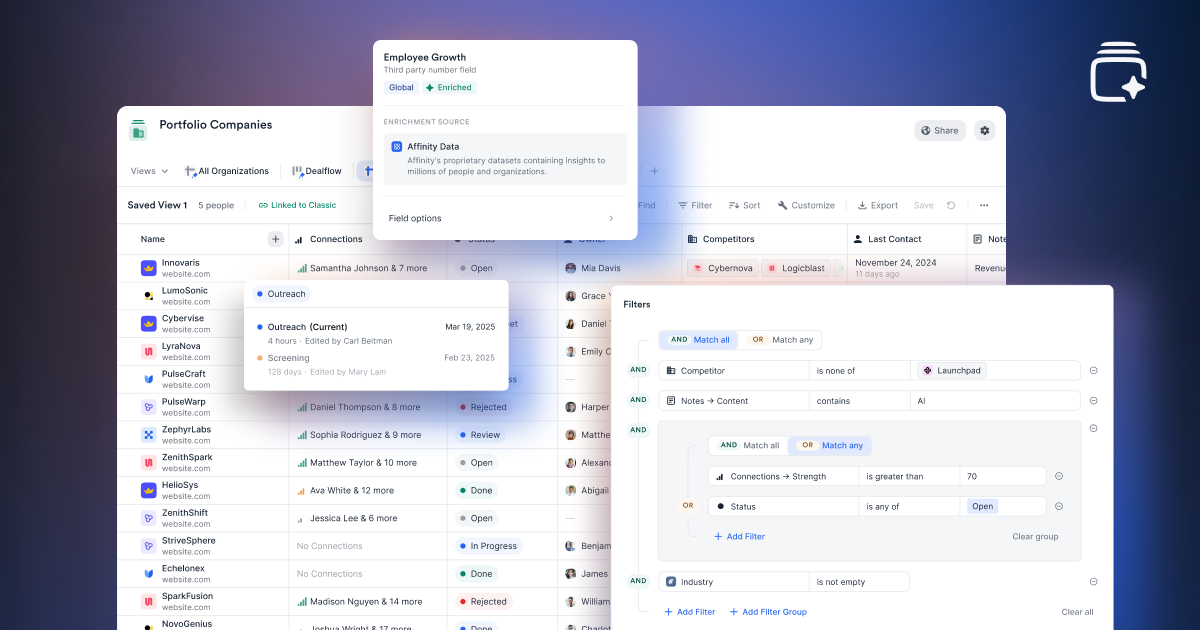

From his home in northern California, Chaddha discusses how investors should go about tracking deal flow, the inescapable importance of relationship management, and drumming up repeat business with the same entrepreneurs time and again.

(This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.)

{{benchmark-report="/rt-components"}}

Affinity: You’re known for being a serial entrepreneur, and you once sought funding for the different businesses you founded in the '90s and early 2000s. In venture capital, how does an investor generate “repeat business”?In other words, how do you back founders on the first company and ensure you'll also be the place they turn for funding on the second company, the third company, and on and on?

Chaddha: Venture capital is a service business. The service and experience you give your entrepreneurs are referenceable in a service business. At the end [of the day], money is a commodity, [but entrepreneurs] have to ask if you’re the best partner to help them build a company.

Again and again, there are examples in our portfolio of entrepreneurs we’ve worked with who have come to us the second time they build a company. Sometimes even the third time they build a company.

Rehan Jalil, the founder of SECURITI.ai, is an example of that. We've built this trusting relationship where he feels we’re always watching out for him, always there to help him—we’re his safety net. He doesn't even talk to any other VC when he starts a company. Since 2007, we’ve done three companies with him. The first one was in the telecom infrastructure space.

It was acquired.

“Rather than advertising yourself, the way you add value [is to] just ask the entrepreneurs what their experience was.”

Then he worked at the acquiring company for two years. Then they returned, did a second company, and built it for four or five years. That got acquired. Then he went and worked at the acquirer. They came back again, started a company with us four years [ago], and it’s doing exceptionally well.

Repeat business will only happen if you do good by the entrepreneur. It's not only about doing well financially. It's about leading by doing good for their company and employees. The proof is in the pudding. Do they value [the experience you give as an investor]? Then they'll come [back].

Affinity: As specific as you can be, how do you prove your worth as an investment partner?

Chaddha: Everybody says they're “value add.” In my career, I’ve personally invested over the last 18 years in 60-plus companies. I have emails. I have phone numbers. I tell potential partners to go call the people I’ve worked with. Rather than advertising yourself, the way you add value [is to] just ask the entrepreneurs what their experience was.

What should the entrepreneur care the most about? Are top-tier VCs helping their companies recruit [employees]? Yes. Are they helping them get access to customers? Yes. Are they helping them with marketing? Yes. I think that's table stakes among the firms Mayfield competes and works with.

The fundamental question is: How many [investors] can get in entrepreneurs’ zone of trust and help the entrepreneur feel that their firm or an individual is always going to back them, watch their back, and be people first. That's where Mayfield and my value add shines.

Instead of being a board member that they report to, it's more of a consultative, collaborative engagement. So that's how we’ve been able to build the relationship, the brand, and take this service-oriented approach where we put the entrepreneur first rather than ourselves.

Company building is filled with ups and downs, and there will be tough times. Part of the reason I tell entrepreneurs to go ask people we’ve worked with before is so they know who's there when the going gets tough. That's when the real character of an investor or firm comes through.

{{benchmark-report-2="/rt-components"}}

Mayfield meets a few thousand companies a year, and we invest in 10 companies. So, in seven to 10 years, [while] our portfolio founders build iconic companies, we would’ve invested in 70 to 100 others. If they're only going to do one [company]. And we’re doing a lot of work on you, they have to do the work on us.

I ask any entrepreneurs that want to work with us to go do the work. Make sure we’re the right partner. Because my assumption is, if an entrepreneur is good and the idea is good, they're talking to five or 10 [investors]. If they're only talking to you, there's something wrong.

Affinity: Even though you're very selective, many companies each year make it through to the deal consideration phase. I wonder if you could help me understand how you manage deal flow.

What happens after they enter the door as a candidate to invest in? What's the process of how many times you check in with them, and how do you track progress on your end?

Chaddha: With Poshmark, for example, we worked with the entrepreneur six months before he even started the company and basically even introduced him to the person who ended up being the co-founder. Then the entrepreneur pitched to five, 10 VCs. But we’d built the relationship [already] that it was easy to win. So that's one scenario.

The second scenario is a company like Lyft. We knew that the sharing economy—back in 2010 and 2011—would represent a gigantic shift in how ride-sharing or the transportation industry works in the future. So there, we had a prepared mind. We leaned in. The company probably had 10 VCs chasing them. But [we] spent time building the relationship with the founders and had them do a lot of diligence on us. And we did a lot of diligence on them. When a company like that comes and pitches, we can move toward a decision within a week to two weeks.

{{vc-guide="/rt-components"}}

You also have to keep an open mind where you don't have a prepared mind. There could be companies who come to you, and you aren't looking at the space. But the entrepreneur is so compelling, and the opportunity is so compelling, that it makes sense to take the risk.

To do that well, we only evaluate the person. There’s this common theme at the stage we’re investing in: Industries will change, but our focus is on spending time with people either before they start companies, or if an investment opportunity is hard and if you don't know the people, be able to drop everything and spend as much time as you can with them—getting comfortable that they're the people you want to work with.

From then on, you have to tease out what they're looking for in their investors and board members, so you can make sure you can provide that. Don't overstep. Just commit to doing good. You have to make sure there’s an entrepreneur-VC fit because it's a long game, but I believe that if you do good, good happens.

Affinity: Despite your limited scope as an investor, you nonetheless have several companies on the go at once. They all have different needs. They all need different attention. They're all at different stages, perhaps, of their maturity.

What are your greatest tips for investors when it comes to the importance of tracking deal flow and making sure that every investment gets the right attention that it needs at the right time that it needs it?

Chaddha: First and foremost, your responsibility is toward existing companies and what I call “money in the ground.” Because you have to make [an investment] successful if you're going to play a role in making a company succeed, so focus on what you've already invested in first.

And if you feel you have the bandwidth, then you can go after new opportunities. The most important thing I would appeal to investors is empathy. When you're working on a new deal, and you know it's not a fit because you don't understand the market, you're busy with your existing portfolio, or you can't get the ownership, communicate that it's not going to work out rather than leaving them hanging on.

Affinity: You are a fixture on the Forbes Midas List, and the political thing many investors who are so recognized would be tempted to say is that “Oh, it’s a nice honor to be included, but it’s just a list that doesn’t mean much at the end of the day.”

But does appearing on lists like these change— if not how you approach investing—does that change how people look at you in Silicon Valley? Does that change the types of people that come to you for capital?

Chaddha: That's a great question. First and foremost, [a place on the list] is the recognition we get for the entrepreneurs we have invested in. We didn't create the companies. It’s the entrepreneur's idea. It's the entrepreneur who's the founder. We gave them money and advice and support to get the company there.

Now, how does it make you competitive in the marketplace? There are a lot of sources of money. The Midas List is a stamp of recognition for people who are helping entrepreneurs achieve their dreams. It's like going to university, right? If you’re a student and you're applying, you might look at a US News list of the best schools.

“If I [find out] what’s not working and never offer help or offer empathy, I won’t have great people stay with me for long.”

I do think entrepreneurs look at the brand of the individual [investor]. They look at the brand of the firm. They look at [ the Forbes Midas List] and think that with a VC on that list recruiting [employees] will be easier. Getting follow-on round [financing] will be easier. Selling to customers will be easier. Because of this, VCs who are lucky enough to make this list because of their entrepreneurs do benefit from it.

Affinity: You’ve talked often about investing globally and keeping a diverse portfolio. Do you have a certain percentage of your investments that you want to be spread across regions or verticals that would represent to you a properly balanced portfolio?

Chaddha: Sector diversity is always important because if you’re dependent upon one sector and that goes bust, it can be a problem. And the relative percentages [of what investors should hold] keep shifting [based on] where you believe the opportunity over the next seven to 10 years is.

When we’re thinking over our investments, we have to consider how much should we invest in enterprise [business] or consumer [business]. How much in human health? Sustainability and planetary health? Web3? It's not equal.

Half of our portfolio over the last five to seven years has been focused on investing in companies that have business buyers. This includes the full enterprise tech stack, from semiconductors to systems to data to middleware and developer tools, all the way to apps.

Affinity: You’ve famously worked with people like Bill Gates, Steve Ballmer, and Satya Nadella at Microsoft—not including all the prominent entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley that you've invested in. What are the common traits of the founders and entrepreneurs that reach that level of success?

Chaddha: First, they have empathy for others. Secondly, they lead with heart.

And then, during times like this, they combine traits of wartime leaders. They act with agility and urgency. They have a bias toward an action mindset, but they still prioritize people and treat them with empathy.

Affinity: You made your fortune with emerging technologies in the '90s, especially video on the internet and broadcasting on the internet. What in your mind are those same still untapped opportunities today?

Chaddha: Web3 infrastructure is a very good opportunity. I'm not talking about DeFi. I don’t mean speculation on tokens, but the plumbing that is needed to move the web from 1.0 to 2.0 to 3.0.

Technologies and companies which are going to reverse climate change and ride the wave of sustainability are the other leaders.

{{benchmark-report-3="/rt-components"}}

And the third area where I am focused on is building developer-first companies where you are more dev-centric, where your [go-to market output] is product-led growth. The process is more bottoms up. It’s all about catering to technologies that the developers use and influence.

Affinity: Your history as an entrepreneur first in your career has given you perhaps a unique perspective among VCs and investors. What tips would you give other investors on how they should best speak to entrepreneurs?

Chaddha: [Entrepreneurs want to hear] that they’re going to be taken care of, that [the investor] cares about them more than the product and the market.

Once people have that, they need to be treated with respect and empathy, because respect is mutual. Investors and entrepreneurs can get into a zone of trust where they can complete each other's sentences as good co-founders do. That makes a difference.

Affinity: What about the flip side to that? If I'm an entrepreneur pitching an investor to secure capital, what are the things that an investor needs to hear from an entrepreneur to make them more likely to provide funding?

Chaddha: Entrepreneurs need to communicate why they're doing a particular thing and understand their company’s values and culture in addition to the problem they want to solve. They also need to know why [their solution] is a painkiller and not a vitamin.

“I do think entrepreneurs look at the brand of the individual [investor]. They look at the brand of the firm. They look at [ the Forbes Midas List] and think that with a VC on that list recruiting [employees] will be easier.”

After that, we try to understand how big the problem is that they're solving. Is it a niche, or is it going to be a mass market phenomenon? As long as the entrepreneurs can start with themselves, their motivations, values, and the culture they want to create they can answer those questions to start. Then move to the problem they're solving. The last part, that directly ties back to the investor relationship is knowing what they need from the investor.

Affinity: You have said that being an entrepreneur is very hard but being a CEO is even harder. How would you characterize that transition from company founder to functioning executive and leader?

Chaddha: When you’re an entrepreneur, you're filled with ideas. You want to make quick decisions. When you become a CEO, a leader, and a manager, you have to make decisions together with your team. You get the final authority to make decisions, but you also have to think of your people. They have to feel they're respected, they're heard, and they're part of the decision-making process.

And you can't be a micromanager. You have to let go and give people space so that they can execute while still feeling that their needs are being met. I always ask three questions when I meet people:

- What's working?

- What's not working?

- How can I help you?

That's what I believe it takes to lead with empathy and leading with the heart. If I [find out] what’s not working and never offer help or offer empathy, I won’t have great people stay with me for long.

Affinity: In your evaluation, what are some of the best deals you've made? Conversely, what are some deals that got away you wish you'd sunk your teeth into?

Chaddha: The deals we’re excited about have been either companies that have succeeded already or exited. These would be companies like Lyft, Poshmark, HashiCorp, SolarCity, Marketo—[these companies] transformed industries.

When I think of opportunities that got away from us, I first think of Nutanix. We didn't understand what the impact on the company would be. We didn't believe in the market. [But] that entrepreneur is stellar, and we ended up partnering with him the second time because he still chose us.

[We] also couldn't get there on Twilio, which is a big, big miss. The same is the case with DocuSign. And that’ll happen when you pass on 99% of the deals. You have to be happy with what you do rather than regret what you didn't do.

Affinity: Let me ask about some of the unicorn companies that you touched on, like Lyft and Poshmark. What do you see in these companies that make you think they are going to become the next big thing?

Chaddha: As I mentioned earlier, it starts with the founders because [investing] is a people-first problem, and once the entrepreneurs are there, double check that the problem they’re solving and the solution they have to make sense. Third, [ensure] there’s a massive market. The last part is making sure they're going to have a competitive differentiator that gives them a four or five-year advantage over the competition. Because if it's only a nine to 12-month [advantage], the world will catch up.

That’s where pattern recognition helps. For example, we were investors in NUVIA the Qual comm bought for $1.6 billion. They had a big, hairy ambitious goal to compete with Intel. And they planned to build the next generation microprocessor for the server and cloud market.

And it came down to the team. The team had built all the Apple iPhone chips for a decade, and also the M1 chips, which were coming for laptops. How many people in the world can build the leading microprocessors in the world? They only exist at Intel, AMD, Apple, and maybe one, or two other companies. So to me, the starting founding team, in some cases, can be inception stage people with domain expertise. They get into a situation where only three, or five teams can do it.

We’re not investing behind traction. We're investing in raw ideas. We have to trust the quality of the team and their approach. Do they have something unique in their business model, something unique in their technology, something unique in their delivery model that the incumbents won't do because it disrupts their own business?

When you’re looking for the “next big thing” you’re not only looking for technology disruption, you're looking for the business model and delivery and [go to market] disruptions, too. You have to because the big established companies, even if they build their technology, they're not going to disrupt their own business. You have to be a true disruptor on many fronts to pull ahead.

If you've not already, read the first part of this interview.

{{benchmark-report-4="/rt-components"}}

.png)

.webp)