This article originally appeared in Forbes.

Product-market fit (PMF) is one of the first and most elusive goals every startup needs to achieve. What’s profound about PMF isn’t how much it matters (it obviously does)—it’s how little everything else matters in comparison to those early days.

There are key tactical decisions and mindset shifts that can determine whether a founder finds PMF or not. These are the three most important things that defined how we achieved PMF at Affinity, the relationship intelligence company I co-founded.

Obsess over the problem, not the solution

Founders need to prioritize thinking about the market and the problem they’re solving, not the product or solution. Many of us are guilty of holding too tightly to solutions when the problem and the market are the real opportunities. The truth is, you’ll have a better shot at building a successful company if you can focus on who your audience is and why they’re feeling pain.

Your first idea of how to solve a problem is just a hypothesis—and it’s usually wrong. It’s important to remember that the product doesn’t exist just to exist or to satisfy your vision and ego. It exists to solve a problem for someone.

This can be a particularly difficult exercise for founders who were engineers and designers beforehand. When you have all of this creative power at your fingertips to make anything you want, it’s supremely easy to get attached to your creations. But that’s the wrong mindset.

Contrast the founder with the artist. In art, the artist is the center of the universe, whereas as a founder, you’re a problem-solver. Your user is at the center of the universe, and your prerogative is to make their lives better.

Go overboard on spending time with early customers

At Affinity, it was luck that had us cross paths with a number of legendary investors in Silicon Valley. These individuals opened our eyes to the world of relationship-driven industries like financial and professional services.

We wanted to understand what these people did and how software and data played a role in it. What we found was almost unanimous: People seemed to hate their relationship management software. If you drew a Venn diagram of the industries driven by relationships and the people who enjoyed using their relationship software, the intersection was practically nonexistent.

After hearing the same pains over and over again, we made it our mission to sit down with as many local financial services firms as we could. We wanted to understand how they operated, whether they would be open to a new solution and, if they were, to literally build the product with them. We often worked out of their offices to get real-time feedback on our product, observe every point of friction they’d encounter using it and design the next iteration with them.

Unsurprisingly, our first stabs at what we thought the product should be were completely off. We had a list of working hypotheses about which of the sub-pains we’d observed were going to become the killer feature that would keep customers coming back. Some of the highest-ranking sub-pains turned out to be more tolerable annoyances than true pain points.

It was only through spending a considerable amount of time in person with our customers that we converged on the solution that validated our core thesis. That time is invaluable to developing true empathy with your users. You must get to the point where you can literally walk a day in their shoes and understand their psychology as they interact with the people and software in their lives.

It pays off. We soon saw usage that looked more like that of a consumer app than of enterprise SaaS.

You can’t improve what you can’t measure

You need to be able to measure product-market fit explicitly and intentionally. This is crucial because where you set your goal post can make the difference between finding product-market fit or just deluding yourself into thinking you’ve found it.

There are a lot of frameworks for product-market fit, but the best approach depends on the business you’re building. Start from the first principles of your product, ask yourself what an overwhelmingly successful user would look like, and work backward to determine what to measure.

To do this, we worked with each of our earliest customers to define personalized success criteria and metrics. Sometimes, it was a hard metric like product usage or volume of data entry automated, but other times, it was a qualitative, subjective feeling that we converted into a soft metric. For example: “On a scale from 1 to 5, how would you say X problem feels like it’s being solved now?” We tracked these personalized assessments and iterated on feedback until we were crushing these customer success criteria.

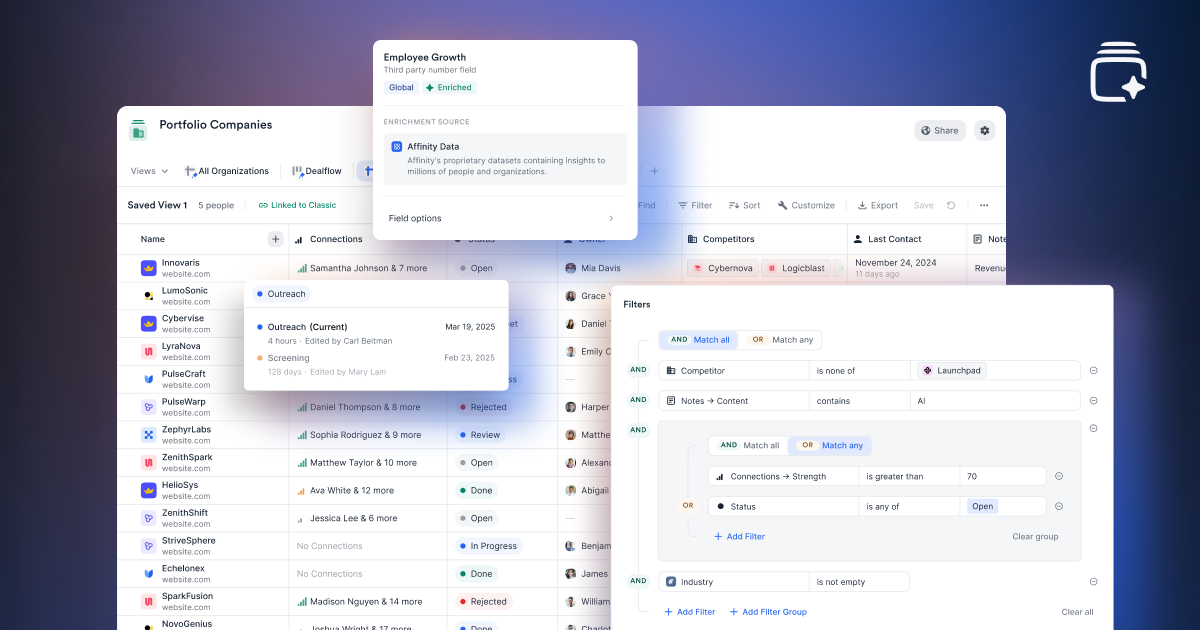

Internally, we also aligned on the metrics that signaled a customer was likely to keep using the product. We set a North Star goal of daily usage, which we felt was necessary to both become a firm’s new CRM and also solve the pain point of lack of CRM adoption. We instrumented those metrics and tracked them diligently, living out of our usage dashboards as well as a session viewing tool to understand the contours of that usage beyond just numbers.

My lesson here is to set overly ambitious goals. Rarely (if ever) can you set too high a bar for customer love. Ultimately, product-market fit is just the first checkpoint on the long journey that is building a company. Think of it like the tutorial level for the video game. If you’re not able to beat the tutorial level, there is no "rest of the game" to play. Stay laser-focused on what matters.

.png)

.webp)